Sex, Lies, and Keyboard Layouts

Take a look the nearest keyboard. Chances are you are looking at a very specific arrangement of Roman letters and various symbols into four rows known as the QWERTY keyboard layout. If you stare long enough, it might occur to you that this arrangement seems quite arbitrary. There are countless ways this could have been done, after all. Why QWERTY?

It well known that QWERTY descended from early typewriter configurations, but why was QWERTY used for typewriters? This very question has been the subject of great debate for nearly a century. In fact, the whole history of QWERTY is rife with disagreement and misinformation. There is no shortage of

blog posts:

youtube videos:

- QWERTY or DVORAK? Debunking the Keyboard Layout Myths

- Why the Dvorak keyboard didn’t take over the world

- History and QWERTY

articles:

- Fact of Fiction? The Legend of the QWERTY Keyboard - Smithsonian

- Why Was The QWERTY Keyboard Layout Invented? - Forbes

- Typing Errors

books:

and academic papers:

- On the Prehistory of QWERTY - Yasuoka

- The Market Process and the Economics of QWERTY: Two Views

- The Great Keyboard Debate: QWERTY versus Dvorak Kathryn Hempstalk

which deliberate on the legend of the QWERTY keyboard layout. Pull up any two of these links and chances are that they will contain two very different accounts on the true history of QWERTY. Simply put, the details of this story are messy.

For me, the detail that has occupied a reasonable chunk of my free time in recent months is summarized by the following question: what were the motivating factors that influenced the development of the QWERTY layout. In other words, we know that QWERTY served to provide a mapping between levers pressed down on a typewriter and the full English alphabet, but what drove its inventors to choose that particular arrangement? While there are many disputed ideas surrounding the history of QWERTY and early typewriters, this particular detail has stood out to me as the most inconsistent “fact” in the conversation about QWERTY. Everyone had their own version of why QWERTY came to be. It became addicting to try and figure out what was really going on, because every time I thought I was starting to get it I would come across something that would turn my understanding upside down.

The most common theory on how QWERTY came to be is that the keyboard was designed to help address some mechanical difficulties in the typewriter’s inner workings. However, even this common theory has many variations and inconsistencies across retellings. For example, some say that the keyboard was intentionally designed to slow down typists, others say there that the keys were arranged to separate common letter pairings, and an old man reminiscing on his insignificant role in the shaping of the first typewriter offers yet another explanation, which we will present and dismantle later on.

One of the few consistencies in later conversations about QWERTY are references to the Dvorak keyboard layout. This keyboard layout was invented with the intent of fixing the inefficiencies of the QWERTY layout, and its inventor would frequently give his own version of the story on why QWERTY was designed poorly. Despite great efforts by this inventor, the new keyboard never took off and would later become the subject of an example of market inefficiencies in economics textbooks. It is suggested that QWERTY remaining dominant over the Dvorak layout is an example of path-dependence, the idea that the market is subject to arbitrary historical forces rather than being a maximally efficient system.

I personally have come to believe that the Dvorak keyboard layout and its aggressive advertizing campaign popularized the ideas put forth by its inventor are the primary source of the modern discourse about the inefficiencies of QWERTY. Dvorak’s claims were not substantiated with evidence and his version of the story never had a firm foundation. So Dvorak’s story was free to mingle with other theories and histories about QWERTY, which ultimately produced the soup of inconsistent stories about keyboard layouts we now have today. The economic discussions about the path-dependence of QWERTY may have provided a resurgence in these stories, giving Dvorak’s perspective a second life. I can’t prove any of this, of course, but I hope to at least entertain the reader by walking through these two fountains of QWERTY contention.

In what follows, I’ll present a brief summary of the history of the machine that QWERTY first appeared on, the Sholes and Glidden Typewriter. After that, I’ll take a look at some modern academic discourse surrounding the origin of the QWERTY layout. I’ll look at some of the major talking points and present the most accurate information I have found regarding them. I’ll also respond to a few theories that have been frequently cited despite containing very weak evidence. Next, I turn to Dvorak and his keyboard layout. I’ll take a look at the efforts he went through to demonstrate the inferiority of QWERTY and how they may have effected downstream conversation. Finally, I’ll turn to the economic debate about path-dependence and how it ties into the QWERTY discussion.

Origins

Cicero demands of historians, first, that we tell true stories. I intend fully to perform my duty on this occasion”

- Paul A. David Understanding the Economics of QWERTY: the Necessity of History

In the piece of writing that launched the QWERTY path-dependence debate, author Paul David paints a target on his back by opening with this line in what continues on to be the most hilariously patronizing introduction to an essay I have ever read. I will regale the reader with this character’s writing later, but for now let’s just hope I am not similarly setting myself up for derision when I attempt to present an “honest historical account” of QWERTY. Though, speaking frankly, this is no history of QWERTY. Rather it is more an assortment of relatively stable facts that may help provide a foundation for the rest of our adventure.

There is good reason to be skeptical of any information surrounding this topic. As I alluded to before, where one can find a single opinion on QWERTY so can one find its opposite. For example,

Sholes’ early prototype had an issue where the bars used to collide with each other. So he arranged the keys in a pattern where the most commonly used letters were spread apart.

- What Is a QWERTY Keyboard? - Chris Pollette

Since then, I’ve heard this story [referring to the account written above] repeated a thousand times. So many times, I had assumed it was true. But Jimmy Stamp over at Smithsonian points to evidence released by Japanese researchers that, in fact, the story is bunk.

Without an exhaustive dive into the primary sources, most of which are housed in archives scattered across the country without digital counterparts, the best I can do is pull on a couple of sources that at least claim to derive from primary sources such as patents and correspondence between the major characters of this story:

-

The Original Typewriter Enterprise 1867-1873- Current 1949

-

The Story of the Typewriter, 1873-1923 - Herkimer Counter Hisotrical Society 1923

-

EVOLUTION OF THE TYPEWRITER - C. V. ODEN

Using primarily these three sources, I’ll walk us through the basic story of the invention of the first typewriter by Sholes and friends, the machine upon which QWERTY first entered the world.

In his “Evolution of the Typewriter” Oden outlines several precursors to Sholes typewriter, many of which influenced Sholes’ work. The earliest form of an invention resembling a typewriter mentioned is a writing machine produced by Henry Mill in 1714, although no record of its physical appearance or mechanism remain. Other early attempts at writing machines include:

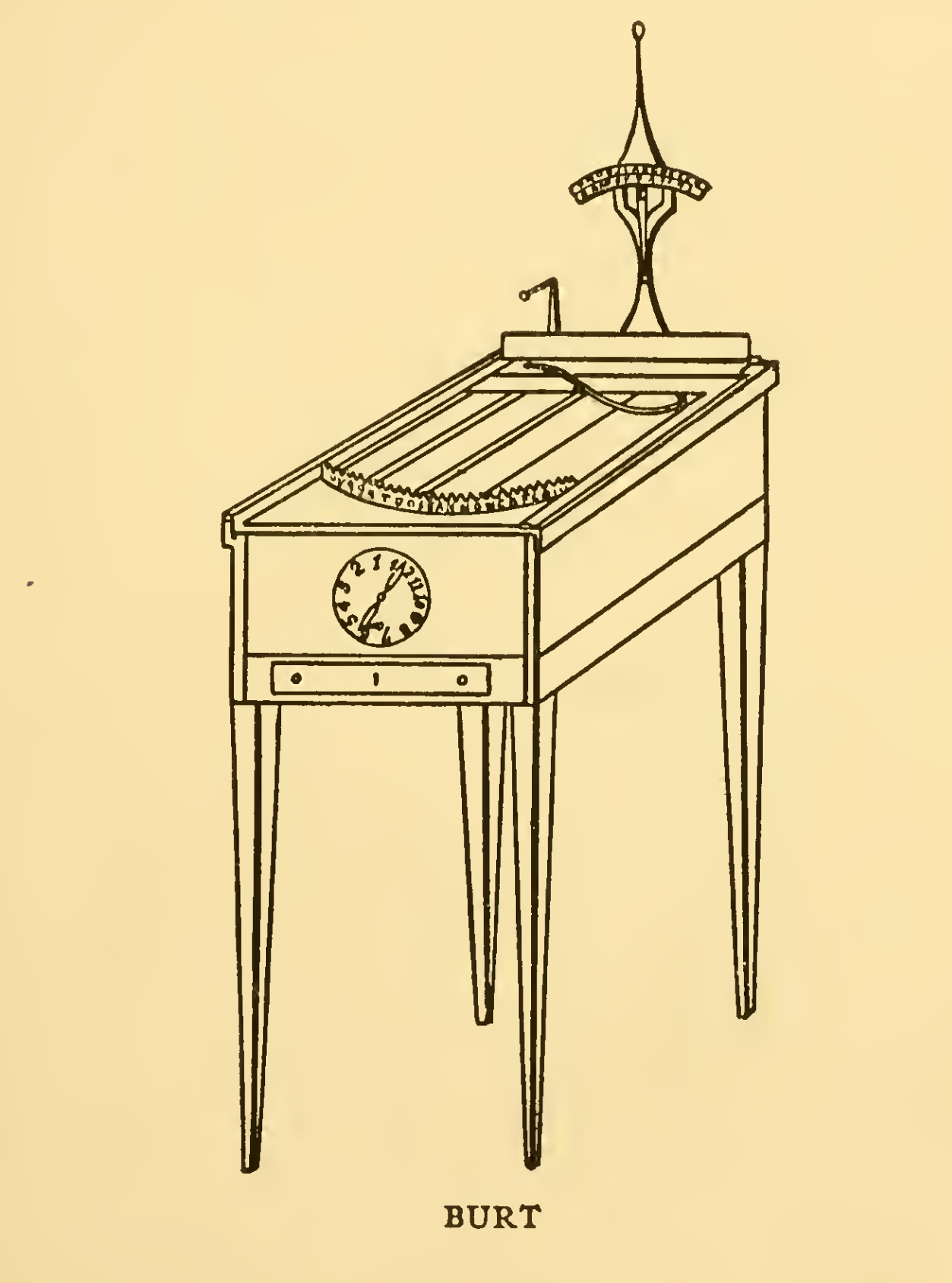

- William Austin Burt who patented a “typographer” in 1829, which had few technical merits and was not successful.

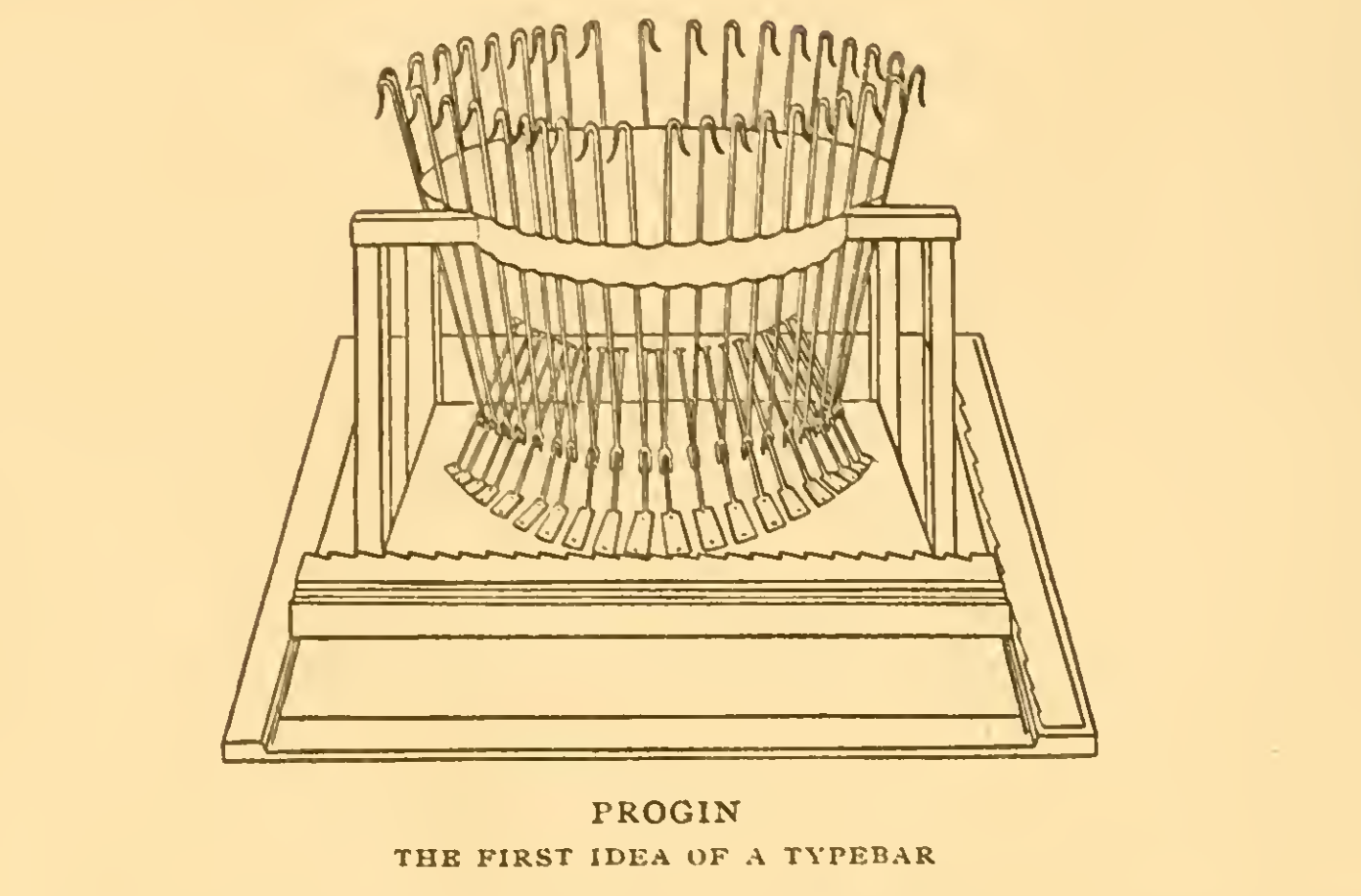

- M X Progin in Marseilles, France patented a ‘typographic machine or pen’ in 1830 and introduced the idea of typebars.

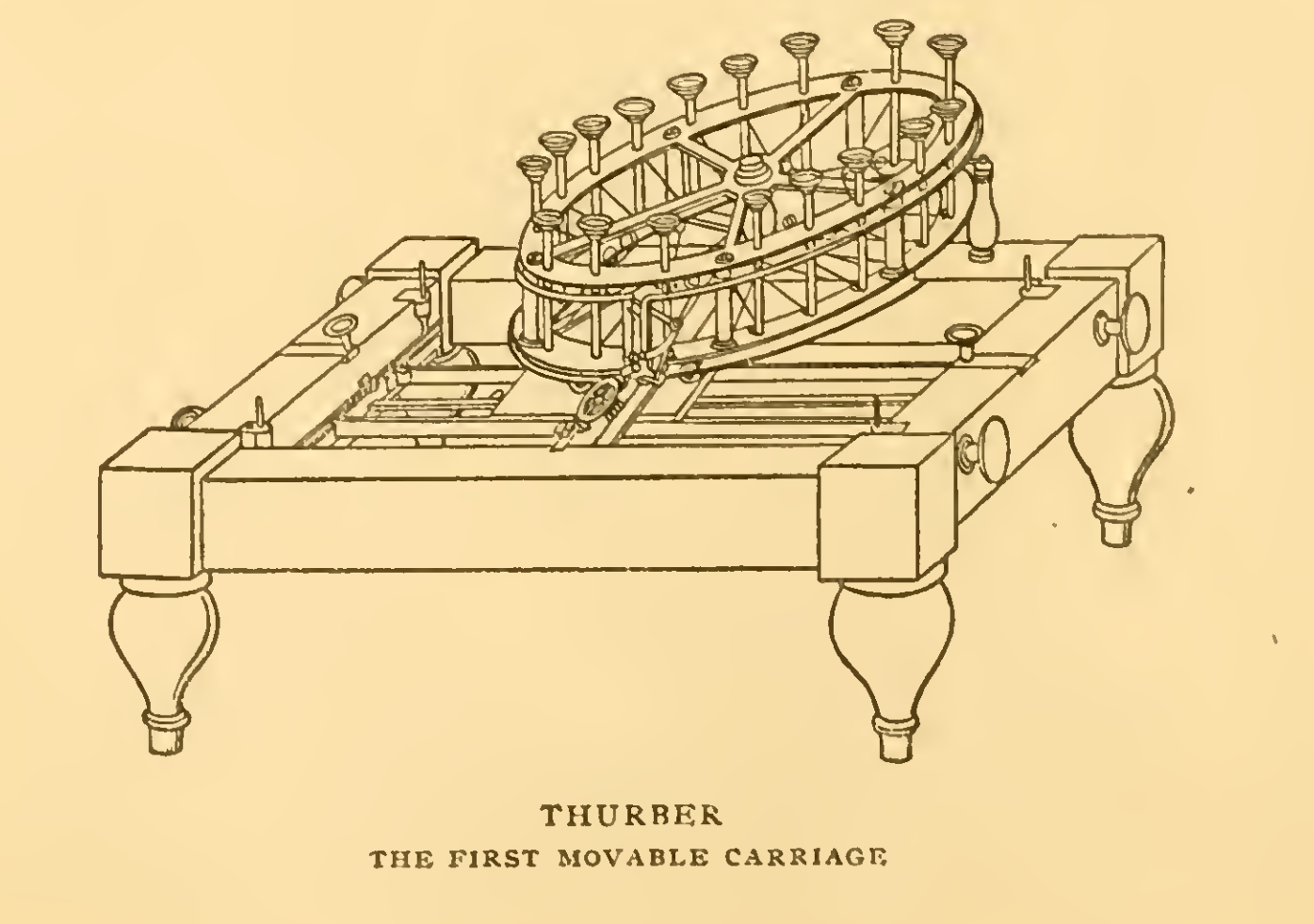

- Later around 1843 Charles Thurber of Worscester Mass invented a working type-wheel machine with a movable carriage (the part of a typewriter that holds the parchment). Again, little business success was realized.

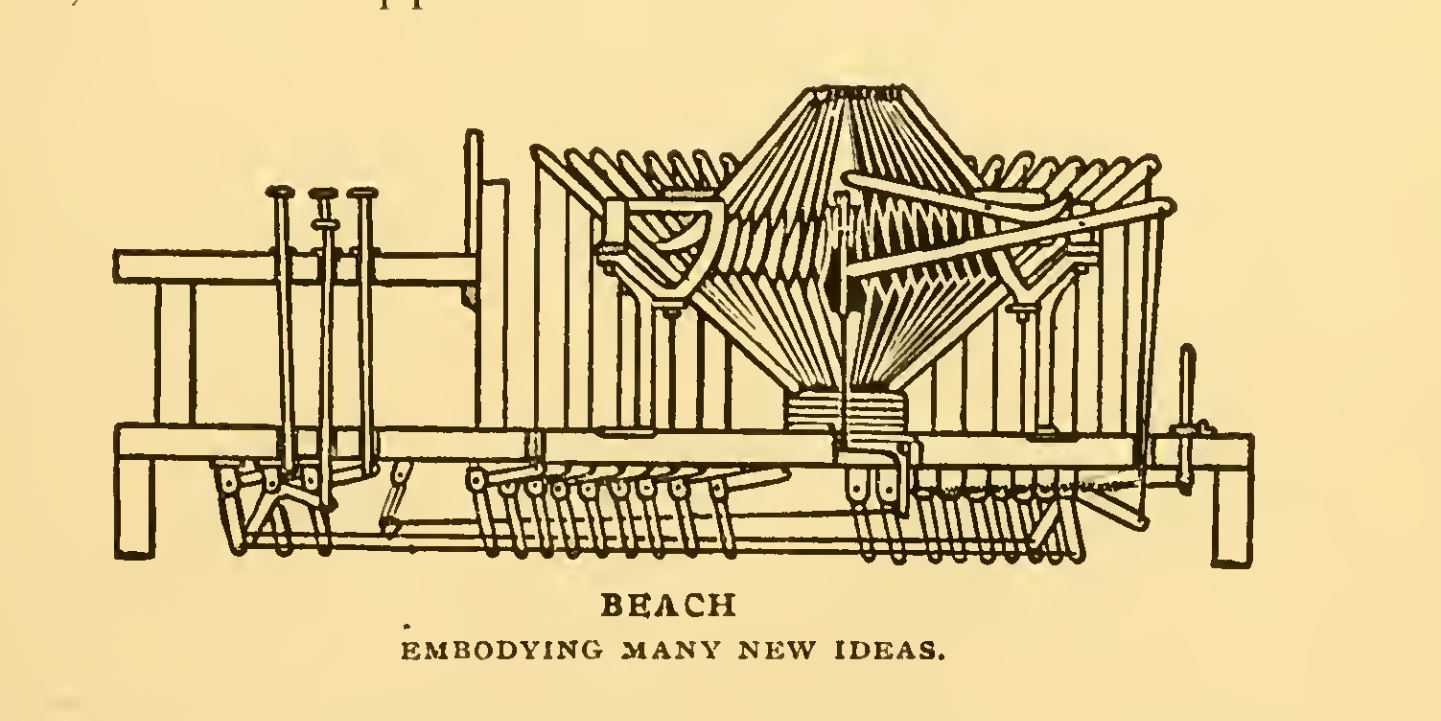

- Alfred E. Beach developed a multiple models during the period of 1847-1856. These machines contained a number of relevant innovations including the idea of a “key stem” or finger key, bell crank, connecting wire, universal bar principle, and convergence of typebars to a common center.

Other attempts can be found in the patent records which, in Oden’s words, “went the way of the many, serving only the purpose of those who fail in their efforts through honest endeavor, leaving an experience by which others may profit.” Perhaps this is a better fate than to face this description:

In 1854 Thomas, an American, invented a machine of such little value, except to suggest a locking device for the type-wheel machines of a later day, that it is hardly entitled to space here.

All of these precursors built towards the historical conclusion of the typewriter we now know. This conclusion was brought about by Christopher Latham Sholes during the years of 1867-1873. Sholes was a deeply humble and well-rounded citizen whose activities included public service and printing, among many others. One fateful day, he read an article that would change the course of his life and the history of the written word.

Shortly after its publication, Sholes read the July 6th 1867 issue of the Scientific American, which featured a “type writing machine” created by John Pratt in England 1. This article featured a call to action, “the laborious and unsatisfactory performance of the pen must sooner or later become obsolete for general purpose,” likely inspiring Sholes’ consequent efforts. Sholes quickly began work on his own writing machine at the Kleinsteuber workshop in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. The shop was second home to Sholes and several of his friends including Samuel W. Soule and Carlos W. Glidden, who encouraged and assisted him in this project.

The first prototype was a demonstration of the key, lever and string mechanism that would convert movement of the fingers to the pressing of type faces into parchment. This contraption contained a single W key and no ability to move the paper across the trajectory of the type faces. Charles E. Weller, chief operator for the Western Union Telegraph Company at the time, was called in to test the device and recounted his experience with the device as follows:

If you will bear in mind that at that time we had never known of printing by any other method than the slow process of setting the types and getting an impression therefrom by means of a press, you may imagine our surprise at the facility with which this one letter of the alphabet could be printed by the manipulation of the key. But while the printing of one letter in this manner was very clearly demonstrated, it was not easy to understand how the principle could be extended to printing words arranged in regular lines, which Mr. Sholes stated could be done, and then proceeded to explain the method.

As time passed Sholes’ prototypes gained some sophistication, and in September of 1867 the first proper model was completed. blah blah. It was around this time that the group reached out to James Densmore to help them finance the project. James accepted. A month later a patent was submitted2 accompanied by this justification of novelty:

Its features are a better way of working the type-bars, of holding the paper on the carriage, of moving and regulating the movement of the carriage, of holding, applying and moving the inking ribbon, a self adjusting platen, and a rest or cushion for the type-bars to follow.”

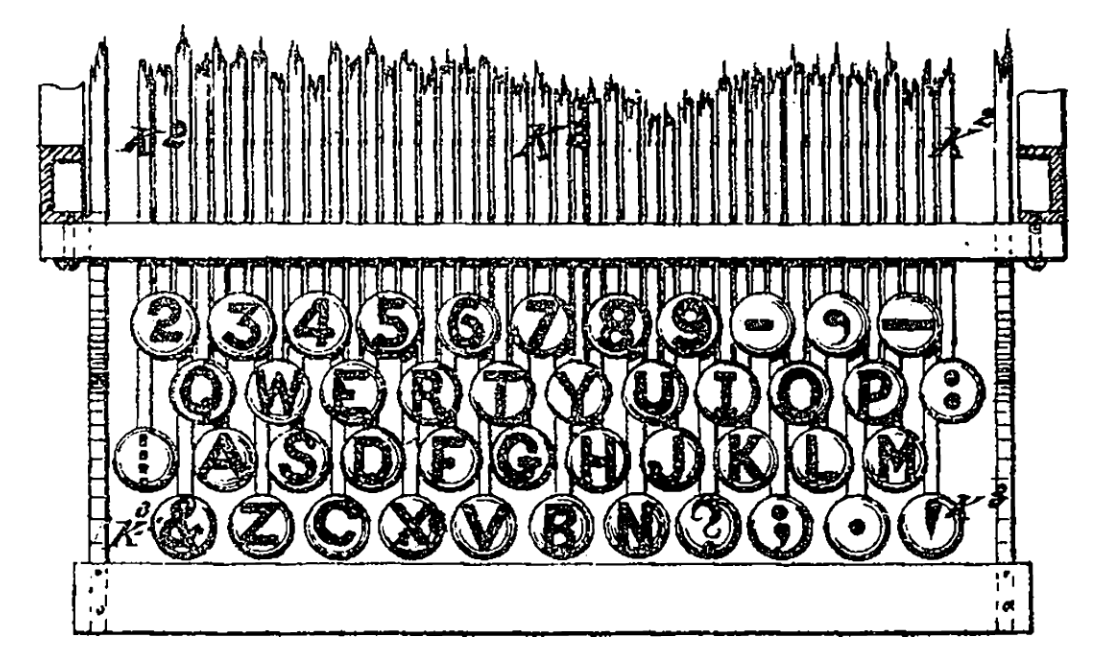

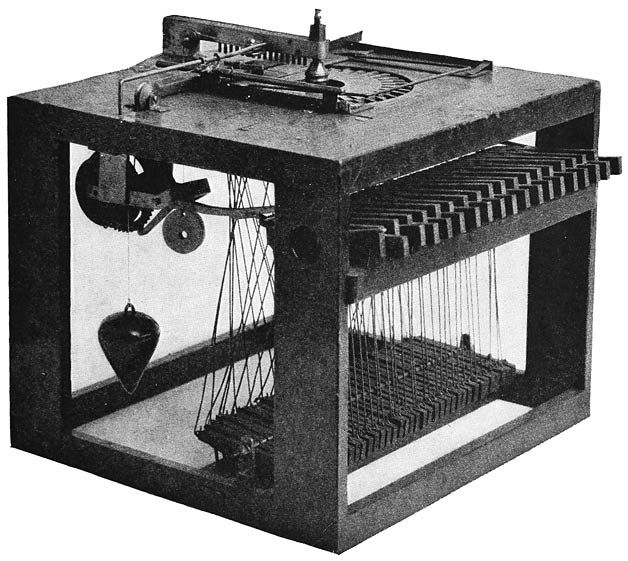

In fact, Sholes’ first patent for this endeavor was not for the invention of the typewriter itself, but for the numerous improvements he developed on the designs of his predecessors. It featured 11 piano keys, six white and five black, and demonstrated the fundamental mechanisms that would underpin future designs.

Only a few months later, a more complete design was developed and patented:

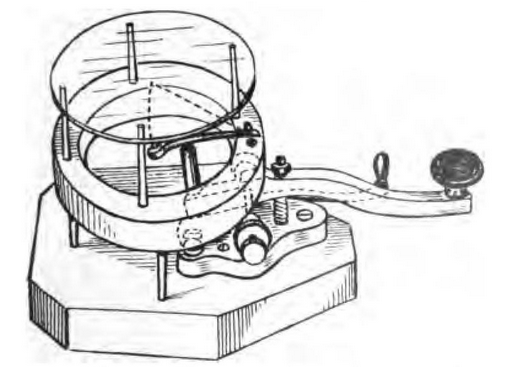

It featured a full keyboard, albeit with only captial letters and still in the piano arrangement. The keys are arranged in alphabetical order from left to right along the “black” keys, and finishing from right to left along the “white” keys. A key feature of this new design is the circular carriage along which levers with type faces at the ends were arranged. These levers were pulled down by the action of the keys, and swung into the center of the device where they make their impression into parchment against the metal fixture hanging above. One can see the counterweight used to bring the levers down on the left side of the device.

Over the following couple of years, Sholes iterated on this design with help from his friends, motivation from Densmore, and feedback from various potential investors. During these years, he struggled greatly with his health as well as feelings of doubt on the feasibility of his design goals and whether or not the final product would be useful. However, a breaking point was reached in 1873 after a prototype emerged of high enough quality to attract serious investors:

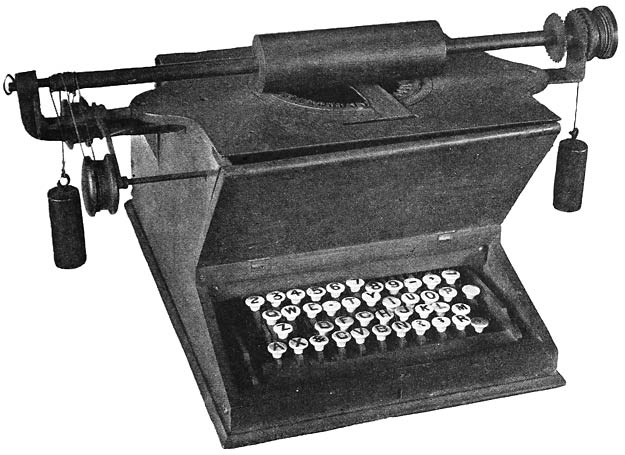

The Remington company - yes, the arms manufacturer - was in need of new products to produce in its factories, now empty in the wake of the end of the American Civil War. This version of the typewriter was presented to the Remington brothers by Sholes’s sponsor, Densmore. After some deliberation and convincing, they entered into a contract for manufacture of the design, which eventually led to full ownership and would go on to release the first typewriter on the market known as the Remington No1.

It is important to note that the model passed to the Remingtons included the more familiar organization of keys into four rows alongwith an arrangement of letters and symbols bearing close resemblence to what is likely sitting before you (or at least only a few touch gestures away from popping up on your phone screen). The mechanisms of the model are not clear in the image provided, but the historian James Inglis has done great work documenting the innerworkings of the typewriter design that was produced by remington, which retains most of the features of the model presented by Densmore. I recommend reading his article for an in-depth understanding of the mechanism. In lieu of that, you can watch this brief video demonstration of the lever action:

Clearly there was a leap made between the alphabetical arrangement on piano keys3, to the QWERTY layout on four staggered rows of keys. What isn’t clear, is the design path through which Sholes travelled to come to the conclusion of QWERTY. I have yet to find a source which attempts to track this progression clearly. Direct references to the keyboard layout in the literature are sparse, and typically isolated when present at all. despite my best efforts, I have not cobbled together a coherent picture of what occured between the alphabetical and QWERTY layouts, nor the motivating factors behind the changes that occured. I shouldn’t be surprised - if a coherent narrative was ready to be extracted, there would probably not be so much confusion as to the origin of QWERTY in the first place. At the very least, I’ll offer one account which comes from one of the oldest, and arguably most reliable sources in the literature:

The truth seems to be that the arrangement of the universal keyboard was mainly influenced by the mechanical difficulties under which Sholes labored. The tendency of the type bars on all the Sholes models was to collide and “stick fast” at the printing point, and it would have been natural for Sholes to resort to any arrangement of the letters which would tend to diminish this trouble. These mechanical difficulties are now of the past, but time has proved and tested the universal keyboard, and has fully demonstrated its efficiency for all practical needs.

- Herkheimer

Versions of this story are the most often version found throughout other retellings of QWERTY and typewriter history. It even persists in some form as the rallying call of alternate keyboard layout enthusiasts. However, as we’ll see in the next section, the truth gets a little more complicated.

Keyboard Layouts

Approximately fifty years after the Remington No.1’s release, a professor at the University of Washington named August Dvorak was advising his student who was writing her master’s thesis on typing errors. While engaging with her on this research, he concluded that QWERTY was a suboptimal keyboard layout.

Not long after this, Dvorak committed himself fully to the development of a better keyboard. He produced the Dvorak Simplified Layout (DSK) which he shared proudly in 1932 through a publication titled “There is a Better Typewriter Keyboard”. In the document, Dvorak describes his account of how QWERTY, or in his words “the so-called universal keyboard,” came to be:

Sholes’ primary problems were mechanical. The action of his machine was so sluggish that to avoid the clashing of typebars being struck in succession he purposely sought to locate in different quadrants of the typebar circle the letters most frequently used together in words. For the modern touch typist, the keyboard resulting from these concepts and mechanical difficulties was one of the worst arrangements possible.

If you have read anything about alternate keyboard layouts, you likely have encountered some form of this story. The retellings vary but the message is the same: the QWERTY keyboard layout arose from mechanical constraints on the inner workings of typewriters and resulted in a poorly optimized layout.

Huh, this sounds familiar. There are a couple of differences though. The first is that instead of claiming that common letter pairs were placed opposite each other, he says the most frequent letters were spread out amongst the four quadrants. A slight deviation from what Yamada claimed, but similar in spirit. The other, more striking difference, is the fervor with which he denounces this design: worst arrangement possible 4. I think this is the key thing. You see, Dvorak goes on to condemn QWERTY by detailing its various failings: slow, clumsy, hard to learn, and ultimately obsolete in his view. This naturally is succeeded by enlightening passages that inform the reader of a better design - his very own Dvorak Simplified Keyboard (DSK).

I call this idea “Dvorak’s Myth”. 5 He is telling us that QWERTY is a peculiarity of bygone mechanical troubleshooting which resulted in a subpar keyboard layout. In my view, Dvorak’s myth is the source of modern QWERTY related conflicts. There is a noticable difference in most of the literature surrounding three QWERTY layout before and after the publication of the myth. Even articles written about keyboard layouts today invariably paraphrase, whether knowingly or not, the above quote as accepted fact. While he was not the first to suggest that mechanical considerations drove the development of QWERTY, he certainly is the first to do so with the intent to convince the reader that QWERTY is a bad layout.

Lies: The Yasuokas

You can find all sorts of refutations of Dvorak’s myth throughout the century that followed the creation of the DSK. One in particular stood out to me because it is so frequently and authoritatively cited. This refutation came in the form of a 2010 publication from authors Yasuoka[^3] and Yasuoka of Kyoto University titled “On the Prehistory of QWERTY.”

The Yasuokas set out to challenge a specific claim made by an earlier researcher, Yamada 6, who suggested that QWERTY was designed to prevent typebars from clashing by separating common letter pairs. This idea has been widely accepted and repeated, but the Yasuokas argue that it’s not supported by the evidence. While I don’t necessarily believe in Yamada’s idea, but I was not impressed by this attempt to dismantle it.

Yamada suggested that the typewriter was prone to jams if two keys adjacent on the type basket were pressed too quickly in succession, and he concludes that QWERTY was developed out of a process which separated common digrams (letter pairs like ER TH CH etc). I invite the reader to explore the images and videos on (this page) to get an understanding of how the letter arrangement could cause jamming.

The main argument from the Yasuokas against Yamada’s theory is straightforward: if QWERTY was really designed to separate common letter pairs, why do we find frequent pairs like “R” and “E” placed right next to each other? It’s a reasonable question. However, they undermine their own point by acknowledging that the “R” key was moved next to the “E” later in the design process, supposedly to allow salesmen to easily type “TYPE WRITER.” This suggests that the original intent might have been different, but the final design was altered for marketing reasons-something that doesn’t necessarily refute Yamada’s claim about the original design process.

The Yasuokas also point out other problematic letter pairs like “A” and “N,” or “I” and “T,” which they argue are not optimally separated. However, when you consider the constraints Sholes was working under—trying to separate multiple frequent pairs while also accommodating other design needs, like placing “I” near the numbers to serve as the numeral “1”—it’s clear that perfect separation was impossible. Some compromises had to be made, which doesn’t necessarily disprove Yamada’s theory; it just complicates it.

Turning back to Yamada’s paper, where did he get this claim anyways? He references an article that was mentioned earlier: The Original Typewriter Enterprise by Richard Current. So let’s see what that book has to say about all this (the “he” in the quote is James Densmore):

To lessen the nuisance of type-bar collisions, which were frequent, largely because of the alphabetical order of the keys, he adopted a new arrangement that he and Sholes had worked out. This revision fixed, once and for all, the basic pattern for the present standard or “ universal “ keyboard.

This is the only mention of the jamming problem and its effect on the keyboard layout in Current’s article. There is a mention of jamming issues on the original alphabetical layout, but nothing of digrams or frequencies. It would be natural to conclude from this that there was a lack of scholarly rigor to Yamada’s paper. But let’s be generous and go a bit deeper.

Where did Current say he got this information? In his article, Current attributes lists of citations for each paragraph in footnotes. I’ll briefly summarize all of the citations associated to the paragraph to which the above quotation belongs:

- A letter from Sholes to Barron (a relative of Densmore’s) June 9, 1872. A copy of this article can be found in the Story of the Typewriter, also previously mentioned. Nothing relevant here. Rather it was highlighted in the Herkheimer book as an example of Sholes’ “not infrequent fits of deep despondency.”

- Another letter from Sholes to Barron Oct 5. 1872. I have not been able to find a copy.

- A letter from Densmore to Barron Nov. 8 1872. Again, no copies found.

- Densmore to Lavantia Douglass (his sister) September 9, 1884. No copies.

- Henry W. Roby’s Story of the Invention of the Typewriter by Milo Quaife 1925 pages 67-69. These pages provide the evidence for other facts mentioned in the same paragraph - nothing related to key arrangements.

Without access to the letters it’s hard to say anything conclusively, so I decided to dig around the Roby book a little more. I was surprised to find following comment:

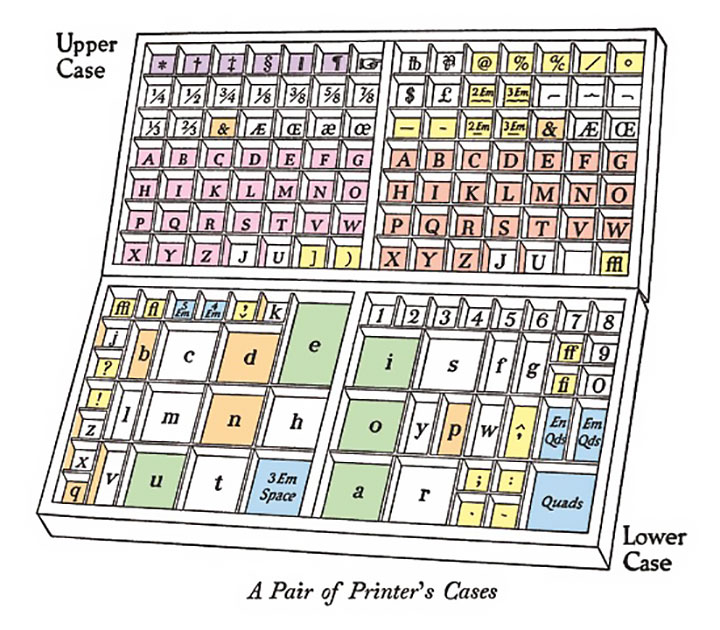

At first the keys were set in alphabetic order and we found certain keys colliding and jostling with one another, but Mr. Sholes, being a practical printer, said suddenly one day as we were talking it over, “I’ve got it!” And while he did not, like Archimedes of old, rush out naked, crying, “Eureka! Eureka!” yet I imagine he was about as happy. He said, “I’ll arrange the keys like a printer’s font and then they will keep out of each other’s way.”

Take a deep breath: right now we are looking at Roby’s book which is cited in Current’s article which was ostensibly the justification for Yamada’s theory that Yasuoka and Yasuoka set out to refute in their paper. If this feels stupid, you’re probably onto something.

Too bad though, on with stupid. The quote from Roby’s book piques my interest for the following reason. This is the earliest source I have found for a different, commonly told story about how the QWERTY layout came to be. The story says that since Sholes used to be a printer, he drew inspiration from the organization of type cases to arrange his keyboard. However, most sources don’t give the story much credit. For example, here is the Herkheimer book on the matter (“universal keyboard” is a reference to QWERTY):

Too bad though, on with stupid. The quote from Roby’s book piques my interest for the following reason. This is the earliest source I have found for a different, commonly told story about how the QWERTY layout came to be. The story says that since Sholes used to be a printer, he drew inspiration from the organization of type cases to arrange his keyboard. However, most sources don’t give the story much credit. For example, here is the Herkheimer book on the matter (“universal keyboard” is a reference to QWERTY):

The usual a b c arrangement of letters, which would naturally suggest itself to the ordinary layman, means nothing to a printer, who is more familiar with the arrangement of the type in the printer’s case. Here, however, we encounter the fact that the arrangement of the letters on the universal keyboard is nothing like the arrangement of the type in the printer’s case.

Yamada chimes in on the matter in his article:

The often repeated story that Sholes arranged the keyboard according to that of the printer’s type box had no foundation, as a closer examination of the latter quickly reveals.

Roby’s legend is a precursor to the one we are dealing with presently. However his story seems to be universally dismissed, whereas Dvorak’s myth is still a modern topic of debate. Sadly, Despite countless hours chasing down references online, I still struggle to make any attempt at a truth claim about Dvorak’s myth. Articles and books just weren’t enough.

Naturally, I had no choice but to track down the letters: the various correspondences between members of the Kleinstauber crew which are only primary sources on the matter that I know of. If I were to find mention within them of letter frequencies, digrams, or placing letters opposite the type basket, that would settle the matter. However, with the exception of a few, these letters are not digitized for online consumption. So I turned to the services of historical archives. The Wisconsin Historical Society Library Archive houses a collection of letters authored by Sholes between 1869 and 1889 and another collection of letters primarily authored by Densmore was listed on the Miluakee Public Museum’s website.

For a small fee, I was able to obtain digitized copies of the letter from the Wisconsin Historical Society. The letters are immensely interesting as historical records of Sholes’ thoughts and feelings during his creation of the typewriter, though I was ultimately disappointed by the total lack of mention of keyboard arrangements in the letters. While the letters at the Miluakee Public Museum were not available for digitization, the curator offered to inquire with a local QWERTY researcher about my interests. My hopes were once again dashed when I was informed that there were a few letters with minimal info about keyboard design but the researcher didn’t recall anything about mechanical arrangement. I happened to have a work trip in Milwuakee, but the curator was not available to schedule an in-person viewing of the documents so all I got was a picture in front of the museum.

For a small fee, I was able to obtain digitized copies of the letter from the Wisconsin Historical Society. The letters are immensely interesting as historical records of Sholes’ thoughts and feelings during his creation of the typewriter, though I was ultimately disappointed by the total lack of mention of keyboard arrangements in the letters. While the letters at the Miluakee Public Museum were not available for digitization, the curator offered to inquire with a local QWERTY researcher about my interests. My hopes were once again dashed when I was informed that there were a few letters with minimal info about keyboard design but the researcher didn’t recall anything about mechanical arrangement. I happened to have a work trip in Milwuakee, but the curator was not available to schedule an in-person viewing of the documents so all I got was a picture in front of the museum.

Sex

Let’s recall a name that was mentioned earlier: Paul David. I used his pretentious paraphrase of Cicero to open my own account of the history of Sholes’ typewriter and also tried to find evidence of Dvorak’s myth by combing through his references. It is time to talk about his essay.

There are a few good reasons for doing so: 1) David’s article spawned a new debate surrounding keyboard layouts which is a fascinating parallel to what we have already discussed with Yamada and the Yasuokas. 2) In his essay, David shares a similar snobbery towards QWERTY that Dvorak expressed in his attempts to supplant the reigning keyboard layout with DSK. This further supports my belief that Dvorak’s attitude and stirring style of critique has meaningfully impacted the discourse surrounding QWERTY even in the present day 3) The article is just insane. The introduction in particular is Tumblr levels of shitposting. Spending $15 on Amazon to get access to these pages was worth it just by the merits of being a ridiculously entertaining read.

About my article’s title and this section’s subtitle. Let me explain. It’s not just click bait. There really is sex to be be found here. Paul A. David talks about sex in his economic history of QWERTY. In his QWERTYnomics, if you will. I took the liberty of scanning the essay so that it can spread across the Internet as it rightly should: Understanding the Economics of QWERTY: the Necessity of History. If you have been at all entertained by this story so far - I’m assuming you have been if you are still with me - then I strongly recommend that you read it yourself. At least the introduction. Regardless, I will give a sampling of David’s unique style of, erm, conveying information.

To give some context, David belonged to a supposedly oppressed subgroup of economists known as economic historians (or historical economists, I am not really sure). Their basic idea was that history was a necessity for fully understanding economics, a premise which the rest of the economic discipline was hesitant to accept. With this chip on his shoulder, David writes the following in the essay’s introduction:

If you are a straight economist and public mention of the subject of instruction in economic history does leave you feeling edgy, let me suggest that you can make these proceedings more comfortable by substituting ‘Sex’ for ‘History.’ Whatever else happens, this should help you to keep your bearings - which often is difficult to do once you get deep into a methodological discussion.

and later:

Actually, if now we have agreed upon the notation: economists = ‘parents,’ economic historians = ‘children,’ and history = ‘sex,’ what Thurber and White’s book has to say is quite suitable to the present occasion.

The book he mentions here is titled Is Sex Necessary? or Why You feel the Way You do. One final excerpt:

To paraphrase the advice in Thurber and White’s manual: ‘When imparting sex knowledge to one’s parents, it is of the utmost importance to do it in such a way as not to engender fear or anxiety.

Absolutely hilariously befuddling.

Putting David’s strange sex analogy aside, what is his essay really about? Well, it centers on the idea of path dependence which amounts to an attack on the idea that free markets are self-optimizing because the free market is subject to arbitrary historical forces. His example par excellence is the QWERTY keyboard layout. The logic is: if the free market is truly optimal then DSK should have been chosen as the primary keyboard layout over QWERTY, however this didn’t happen so the free market cannot be optimal.

Latent in his logic is the assumption that Dvorak is superior to QWERTY in a way that is meaningful to the market. David’s primary piece of evidence for this assumption is a study by the U.S. Navy conducted in 1944 to assess the benefits of switching from QWERTY to DSK. The study found that it took about 52 hours of training for typists to make the switch and that typing speeds and accuracy increased by about 70% after transitioning.

David’s strangely formulated attack on market optimality unsurpringly ruffled some feathers. In 1990, five years after David’s essay was published, academics Margolis and Liebowitz responded to David’s essay in an article titled “The Fable of the Keys”. Rushing to the defense of the market, they point out that the Navy study was not able to be replicated in a similar study carried out by the U.S. General Services Administration in the 1950s. Furthermore, since Dvorak himself was involved in the Navy study, they suggest that the original study was likely biased towards a positive result for DSK.

In addition to dismantling David’s key piece of evidence, the article contains a thorough argument against David’s position on path dependence. Unpacking all of that would require getting into some of the details of economic theory, which frankly isn’t an exercise I really care to do. If you are interested in watching two articulate economists meticulously tear down David’s polemic, I invite you to check out the article.

David never recooperates from this rebuttal, despite his attempts in to do so in hist 1999 article “At last, a remedy for chronic QWERTY-skepticism!”, and is further mocked in a follow-up article from Margolis and Liebowitz titled “The Troubled Path of the Lock-in Movement”:

While he initially appeared to claim that he would respond to our criticisms of his keyboard paper, he has failed to do so and now says there is no point in doing so. Surprisingly, he also claims that market failure was never an important part of his QWERTY argument.

To be clear, I am only commenting on the optics of the back-and-forth - without a dive into the economic arguments I really can’t offer an opinion on who is right here.

Closing thoughts

What I’ve learned is that people are strange. Why does anyone care about this? Why is so much discussion generated about a seemingly mundane detail of typewriter history? I am partial to the idea that Dvorak injected history with a particulary aggressive flame for keyboard layout justice that has persisted throughout the last century. Its not something that is easy prove, but sometimes when I read certain polemics about QWERTY it feels as though the spirit of Dvorak is alive in the text.

I have also developed an appreciation for the complexities of navigating historical truth. Despite giving what I consider a hearty effort, I was unable to establish concrete facts about the motivation behind the QWERTY layout, though I do think I have made some meaningful contributions to the ongoing discussion. Not all hope is lost, though. My interactions with museum curators over email has provided me with the contacts of other QWERTY researchers who may hold the answers which I seek.

Hopefully this was an enlightening or at least interesting read. If nothing else the next time someone at a party talks about how QWERTY was intentionally designed to slow down typists, you will be ready to interject with a confident “well, actually!”

-

Interestingly, one of the editors of the magazine at the time was Alfred Beach, who contributed to the long list of typewriter precursors. ↩

-

Accepted June 23, 1968 ↩

-

However, if you look closely remnants of the alphabetical arrangement can be found in the home row of QWERTY. ↩

-

Fun fact, there exists a genuine attempt at creating the worst arrangement possible: https://mk.bcgsc.ca/carpalx/?worst_layout ↩

-

Myth as in “a set of beliefs or assumptions about something,” not as in an outright falsehood ↩

-

The following two points are quoted directly from the Yamada article both here and in the Yasuoka paper. ↩